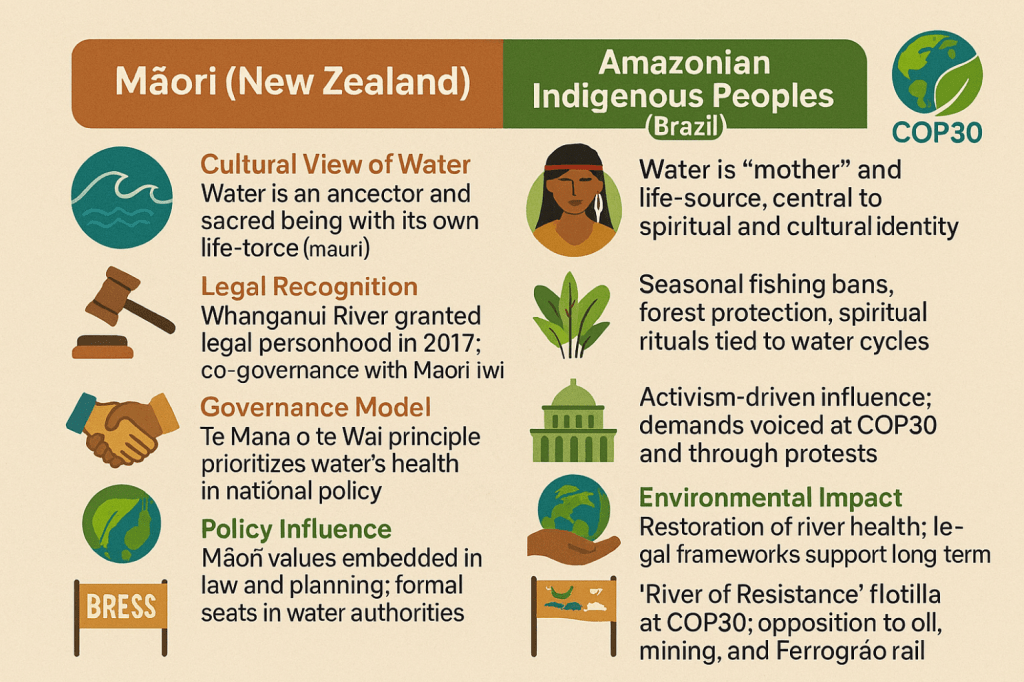

Indigenous communities in New Zealand and Brazil offer powerful models of water stewardship rooted in cultural reverence and ecological responsibility. The Māori of Aotearoa treat water as a living ancestor, guided by the principle of Te Mana o te Wai, which prioritises the health of water above all other uses. This philosophy was embedded in national policy by 2020, and in 2017, the Whanganui River was granted legal personhood, making it the first river in the world to hold human-like rights. Māori guardianship practices such as kaitiakitanga (environmental stewardship) and rahui (temporary bans) have helped preserve water quality and flow. At the same time, integrated catchment management (ki uta ki tai) reflects a holistic approach to ecosystem care.

In Brazil, Indigenous peoples of the Amazon basin, who manage up to 50% of the world’s remaining intact forests, see rivers as sacred lifelines. Their territories, covering 13% of Brazil, have lost only 1% of native vegetation since 1985, making them critical to water and climate stability. At #COP30 Belém, Indigenous leaders led the “River of Resistance” protest, with over 200 boats and 5,000 participants sailing the Guamá River to oppose oil drilling, mining, and the Ferrogrão railway. Chief Raoni Metuktire and others called for respect, land rights, and an end to extractive projects threatening their waters.

Scientific studies support their claims that securing Indigenous land rights could reduce Amazon deforestation by 66%, and emissions would be 45% higher without protected Indigenous territories. These communities also demand Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) for any development affecting their lands, as guaranteed under international law. It was a record increase in visibility at COP30, with over 900 Indigenous delegates. Their calls for direct climate finance and veto power over harmful projects remain urgent.

Comparatively, Māori influence is institutionalised through co-governance and legal frameworks, while Amazonian Indigenous peoples rely on activism and international pressure to assert their rights. Both demonstrate that water security is inseparable from Indigenous sovereignty and ecological integrity. Their stewardship models, centred on respect, intergenerational planning, and community-led action, offer vital lessons for global climate and water governance.

Indigenous communities have long been the vanguards of water security, treating rivers and aquifers as living ancestors or mothers that deserve care, and practising sustainable management that modern science now validates. The Māori of New Zealand demonstrate how honouring this relationship can transform governance at all levels. At the same time, the Indigenous peoples of Brazil’s Amazon show the power of unity and moral clarity in defending the water commons on which we all depend. As the world seeks answers to climate change and water scarcity, embracing Indigenous water stewardship is about enlightened self-interest. It offers a pathway to policies that protect the planet’s most vulnerable ecosystems and ensure that future generations inherit living waters, resilient forests, and the wisdom of those who kept them safe.

#IndigenousStewardship #WaterSecurity #LivingRivers #IndigenousRights #ClimateJustice #NatureBasedSolutions #COP30 #FPIC #EcologicalIntegrity #IndigenousKnowledge #RiverRights #WaterGovernance #ResilientEcosystems